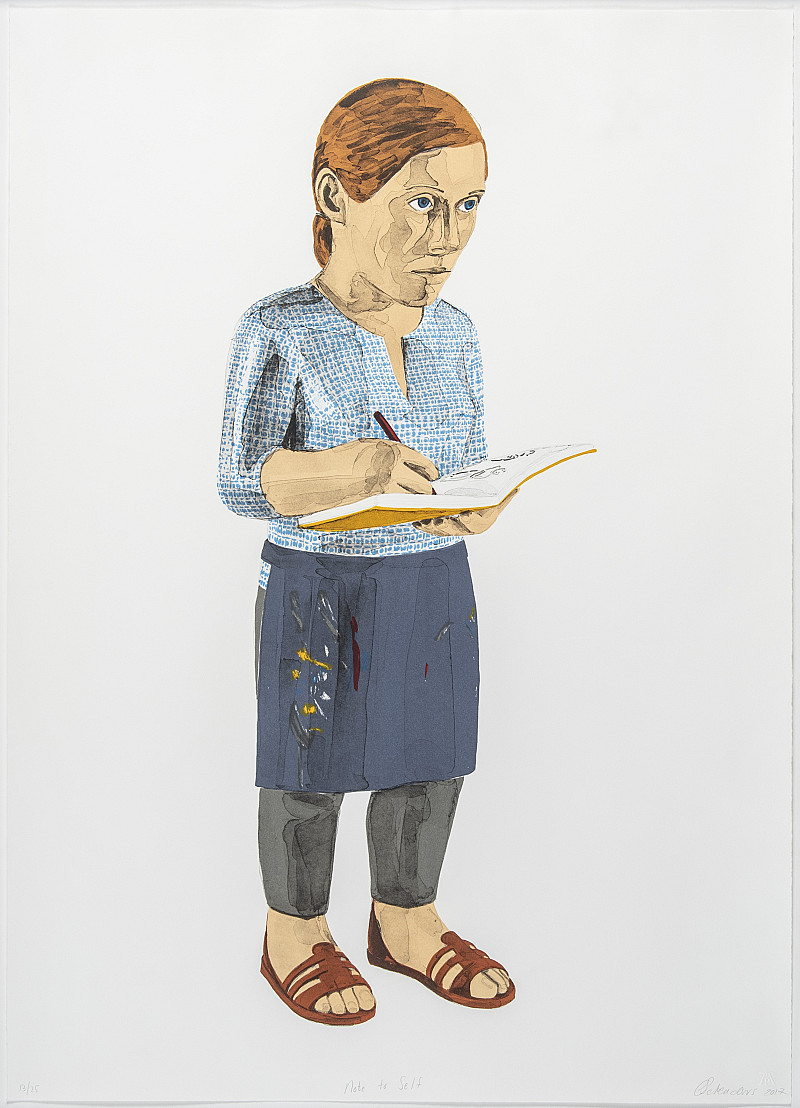

- Note to self

- Claudette Schrewders

- 2016

- eight colour lithograph

- 13/25

- Sheet Size: 90 x 64 centimeters - Image Size: 78 x 31 centimeters

Claudette Schreuders creates carved and painted wooden figures that reflect the ambiguities of the search for an 'African' identity in the post-apartheid 21st century. The domain of woodcarving is a contested one for a white, Afrikaans woman, and the subtractive process of carving offers a certain lack of control that she enjoys. Schreuders sculptures demonstrate a convergence of African and European influences from the blolo and colon figures of West Africa to medieval church sculpture, Spanish portraiture and Egyptian woodcarving. Their stocky bodies, solid stance and staring eyes 'own' space in a very particular way, partly indebted to the shape of the block of wood from which they emerge. Narrative and story telling are fundamental to the reading of her figures, which is why Claudette Schreuders opts to show small bodies of work as sculptural installations, after which the figures are available to be bought individually.

Schreuders sculptures are essentially modern deities for modern problems, taking with them the blolo figures' potential to 'cure', as well as engaging with issues around foreignness and hostility and the means we use to create a space for ourselves in a perceived 'alien' environment.

Schreuders work often follows the theme of making public that which is private or simply telling stories that have their origins in personal experience. It is this straight forward approach to herself, her world and her work that makes the work so moving and appealing. Schreuders is able to make something universal out of the seemingly trivial and personal. Her honesty and sense of humour are evident in the work.

The artist describes herself as something of a perfectionist, working slowly and indulging in her labour intensive process; which she sees as revelatory in terms of understanding one's intentions and desires. "I start off by making thumbnail sketches, very loose simple drawings of what I want to make. And I usually draw my sculptures in groups. Or on small pieces of paper, or in my books. The drawings I do for my sculptures are very informal. And the prints I do are much more finished products. My first series of etchings was a record of some of my favourite existing sculpture. And after that I decided what I would like to do is to keep a record of my own work seeing as it's something that leaves me."

The first set of lithograph prints Crying in Public that Claudette Schreuders did at The Artists' Press sold out almost immediately. The high quality of the lithographs and the intensity of her drawing mean that those who cannot afford her sculptures are still able to build up their collections of this remarkable South African's work. She has continued over the years and arrival of her children to keep a record of her sculptures in lithographic form.

In 2004, Schreuders was commissioned to do four life size bronzes of South Africa's Nobel Peace Prize Laureates, Nelson Mandela, Desmond Tutu, Albert Luthuli and F.W. de Klerk for the Waterfront in Cape Town.

"I think what I'm interested in is telling stories. It's portraiture, but it's a vehicle for telling a particular story, or the way in which society makes people who they are, or the group against the individual. As soon as you make a figure, it has an identity, and it's immediately a white person or a black person. To me, things aren't that simple in South Africa. Everyone has an identity. And I made three white figures at first. The first one was Lokke and then the Housewife, which was fibreglass, and then the Dominee, which was of my grandfather. And then you start thinking, "but they're all white". That was before I even looked at the colon. And that provided a connection for me in Africa. I like to think of it as desire in a way that makes you want to make things. I don't look for 'authentic African art' to collect. I find that relationship of 'taking' very hard. My whole outlook is obviously western, but if you do research about art, or your own art, you have a whole different way of looking at it. Then you can get back to very basic questions. It's interesting for me to look at portraiture as something where you try and make a person with the idea you have of them, and try and bring in abstract elements, like in African art where they say "this is a beautiful person because he [sic] is complete." So I am interested in making things that are beautiful, and how beauty works." Claudette Schreuders